PEAK CRINGE

If social video is our universal language, cringefluencers are mainstreaming its metafictional slang to fulfill an old Toronto School prophecy of network society.

You’ve seen it, you’ve scrolled through it, you’ve hated it, thanks: from insufferable female leads to unironic boy bands, from Barstool neurotics to queer thought leaders, from your evil stepmother to your deranged coworker, cringefluencers are the aspirational heroes of the creator economy. It’s based to be cringe, and the art of embarrassing yourself wields tremendous online influence, winning creators huge followings, podcasts and partnerships. You don't even have to be a comedian. Soon, everyone you know will be posting cringe, and it may even be intentional.

What’s so enviable about performing debasement? Pop-psych from the bestseller list to Taylor Swift indicates it’s the emotional courage of the performer that produces an onlooker’s cathartic hit of mortifying recognition. But performance strategies don’t emerge from nowhere, and the iceberg tiers beneath peak cringe indicate another, much less conscious story: one of mass video literacy reshaping the world in real time.

PART 1: THE LURE

“They became what they beheld.” - William Blake

The effective big bang of peak cringe is “the Lore”, an extended video narrative that took place on the Instagram and Tiktok accounts of New York-based performer Veronika Slowikowska, created alongside actor Kyle Chase and filmmaker Michael Rees. The Lore (internet shorthand for backstory/canon) casually serializes the popular cringe comedy performance videos on Slowikowska’s actual account into a strangely formal “will they or won’t they” saga in which Veronika devolves step by degrading step in the monomaniacal quest for ‘roommate’ Kyle’s heart.

Veronika undermines Kyle’s then-girlfriend; Veronika follows Kyle onto a plane; Veronika take over Kyle’s film shoot to declare her love; Rees is incorporated into the love triangle; Veronika gets a sweatshirt with hundreds of images of Kyle’s face; there’s a second Veronika in an accidental Kieslowski connect; more mystical elements enter the fold as the two come together and the saga, now retroactively named as “The Lore”, is closed — but not without a behind-the-scenes documentary featuring a fake director directing Rees, and not before Veronika’s account gains hundreds of thousands of followers, turning her into a bona fide force in comedy and the creator economy.

There’s more to it than Slowikowska’s generational talent. “The Lore” augments cringe bits with an incidental linear TV premise and tastefully reimagines creator economy production hallmarks like the hype house (reincarnated as bit-com apartment) and daily posts (justified through reality show meta-narrative). But more importantly, it inverts the questions which could break down identification with her as an influencer – “Is this real?” – to instead carefully cultivate participation.

The audience is cast as both detectives sussing out backstory and a Greek chorus cheering on Veronika’s race to the bottom, all of which increase our identification with her as a cringefluencer. Sure, some howdeedodats squirm, but alt-comedians and indie filmmakers look on like it’s the moon landing as these serious, dedicated and meticulous artists crack the code for metafiction on main.

Because cringe is, by nature, metafiction — video about videos. For a realist premise (in Veronika’s case, an influencer wannabe) to be undercut by cringe parody, the audience must possess reflexive fluency in such sorts of video premises and the production processes behind them. Just twenty years ago, a small minority of people would have been able to point and shoot and cut, but now that video literacy has reached mass saturation, it’s easier than ever to be in on the joke.

A central axiom: where there is cringe, there is video literacy reaching critical mass thanks to emergent consumer tech. The invention of metafictional social personae has previously been the high-concept province of entertainment brand and social promotional campaigns, most notably in Joe Keery’s Kurt Kunkle for the movie “Spree”, but now effortlessly incorporating metafiction as part of an ‘authentic’ influencer’s content occurs in a much more organic, human and casual way, functioning as a sort of video slang.

As opposed to slang of the written or spoken variety, which exploits and inverts the ever-evolving grey areas of grammar and syntax, the slang of cringe metafiction plays with one of the core tensions of video language itself: the existence of both cameraperson and performer, subject and object, inherently giving every social video account a dual voice.

In the case of The Lore, Veronika’s debasement is entirely framed through the perspective of Rees’ witty, involved role as filmmaker, employing extreme whip pans and voiceovers to create an ultra-subjectivity that exaggerates and underlines the camera’s presence. The viewer, having spent the past 15 years slowly learning the same tools in capturing and evaluating their reality, can’t help but relate to Rees’ real-time emotionality and active listening. This tension underlines the meaningful, core question at the heart of the cringe explosion: who is the true subject of a social video, the performer on-screen, or the camera’s eye? Veronika is the star of the show, Kyle the apple of her eye, but Michael may very well be the lead protagonist.

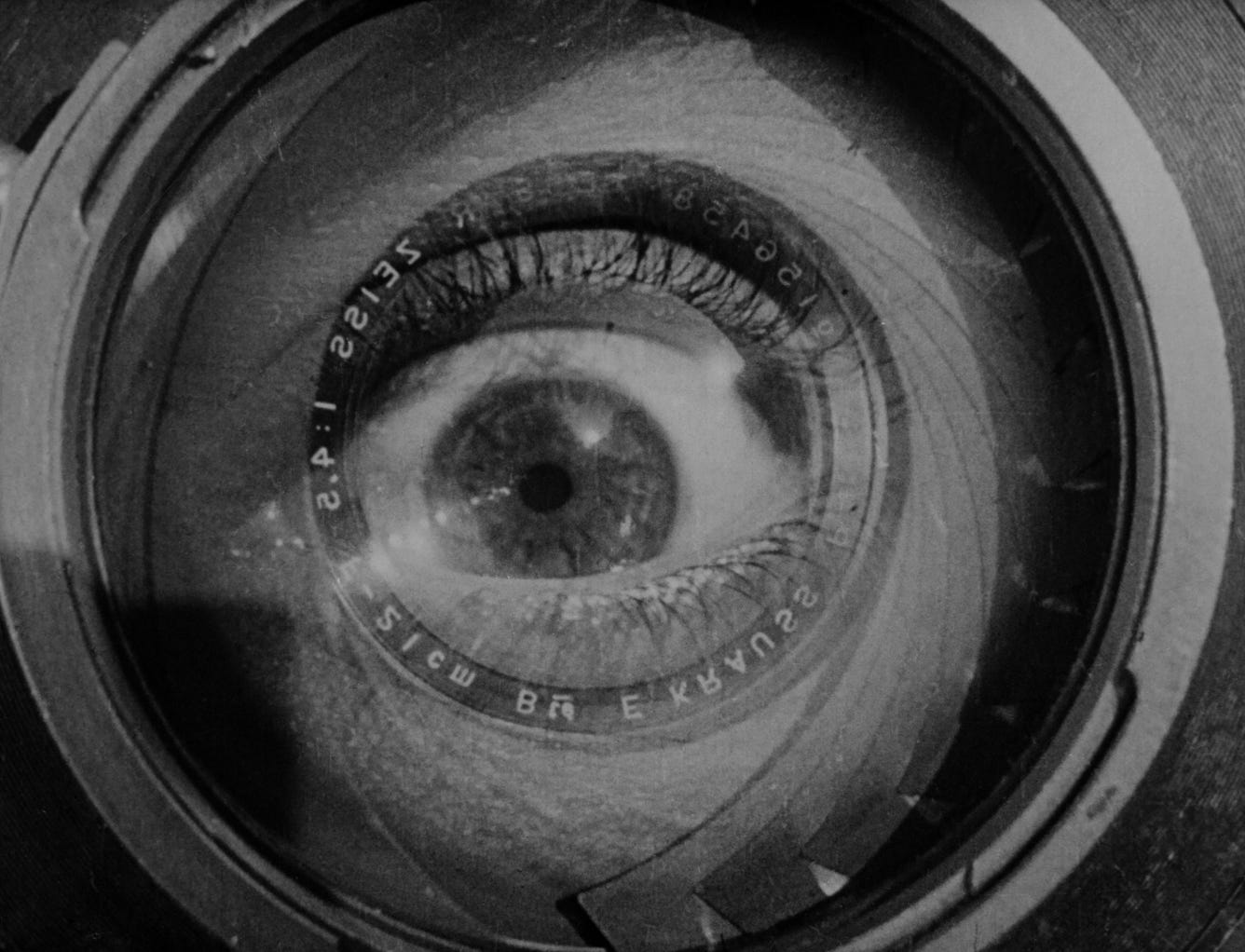

“I'm an eye. A mechanical eye… Freed from the boundaries of time and space, I coordinate any and all points of the universe, wherever I want them to be. My way leads towards the creation of a fresh perception of the world.”

— Dziga Vertov

The early days of a new medium always foreground properties familiar to existing forms, so we first identify with the performing influencer as a facsimile of a movie star. But an instructive referent to the the limits of that identification occurred during the dawn of the original movie camera, when Man with a Movie Camera director Dziga Vertov intuitively de-centered both screen idols and the boilerplate agit-prop of Soviet social realism, instead suggesting that the actual key function of video is in its ability to reveal the point-of-view of the eye in his ”Kino Eye" manifesto.

It’s the eye, of course, that’s the window to the soul, and the age of the camera’s mass reproduction is a proliferation of the eye, of the soul, and by extension folk consciousness. The Lore’s stealth cringe calculus of involved lead camera subject and unreliable performer object in many ways indicates a transitional phase into the major emergent development in 21st century film language: first-person narrative.

Just like mass literacy in the written word eventually allowed novelists to employ a fictitious “I” a la Lolita, mass video literacy enables the filmmaker to construct a fictitious eye, to cast the filmmaker in the narrative, and be understood. Television programs like How-To with John Wilson or Peep Show, documentaries like Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson and recent movies like RaMell Ross’ Nickel Boys and Steven Soderbergh’s Presence approach this idea to profound effect through high-concept means.

But their pro-rigs are ultimately reactive to the source of their audience’s engagement with first-person – the mass adoption of the smartphone – whereas social video cringe meets the viewer where they immediately are. As the cringe performer destabilizes and the subjective camera announces itself, a viewer recognizes the energy of the Lore, sees what they did there and laughs to exchange the core unconscious message: “I am also a filmmaker.” If video is the shared language, then the metafiction of cringe, like all slang, is a badge of identification for the new type of person that uses it: a person defined first and foremost by their kino eye as expressed through social video.

Which means you can only binge so much cringe before you try making your own at home. While one measurement of the Lore’s cringefluence is its microcelebrity blast radius (five years from now, guest characters from Eric Rahill to Delaney Rowe to the Almost Friday cast may well be major Hollywood players), it's more notable that for a new generation, the Lore is the lure to casually express oneself by thwarting one’s own realist first-person influencer scenarios. As Brian Eno said, the Velvet Underground may not have sold many records, but everyone who bought one started a band.

This real-world impact clarifies just why cringe content is so genuinely unnerving: a mainstream embrace of the form’s implicit framework, camera as lead protagonist and performer as destabilized object, communicates a simple, radical message about social media: a place where Vertov’s left-field vision becomes the baseline rule, where video expressiveness supersedes traditional reality.

That question – “Does video expressiveness supersede traditional reality?” – is the decoded meaning of the classic reactionary response to cringe – “Is this real?” The radical challenge to tradition that the reaction correctly detects is an implication that “authenticity” itself is a performative social fiction. From this jumping off point, cringe adds: “So why not formalize it?” In its video conscious reversal, authenticity itself is the heightened conceit, and Wes Anderson the one who is completely naked; social capital is actual, and an online audience might actually be more relevant than a momentary living situation; performing debasement may not just be a joke but a signal that the online me, the video-expressive me, my eye, is realer than the character I play.

Such a depraved, cynical and unholy sign of the times paints a picture of people speaking video as network citizens first and foremost, destabilizing prevailing concepts of property, family, religion, and order. To take this as prophecy rather than provocation, one would need to truly believe in the structure of media as a determining factor in composing human life and identity much more than is currently widely accepted.

That’s why, to my Kino eye, the most interesting guests from the Lore saga may well be the extended universe of comedians featured in and/or loosely connected to Slowikowska’s work based on her comedy career before moving to New York — comedians like Mitch Wood, Ben Stager, Sam Burns, Nathan Hare, and Mark Little – who paint a picture of a city historically receptive to this perspective, a city far cringier per-capita than any other in the world.

It’s a novel concept to someone like me, too. But then again, I’m not from Toronto.

PART 2: TORONTO SCHOOL

“Humor is often prophecy.” - Marshall McLuhan

Deconstructing a joke is like pulling teeth. To intrude on our last refuge of play with serious inquiry smacks of bad-faith mind policing or “comedy is the resistance” self-regard. And suggesting cringefluencers like the Toronto native Veronika Slowikowska are media prophets reshaping the world through soft power offends on principle.

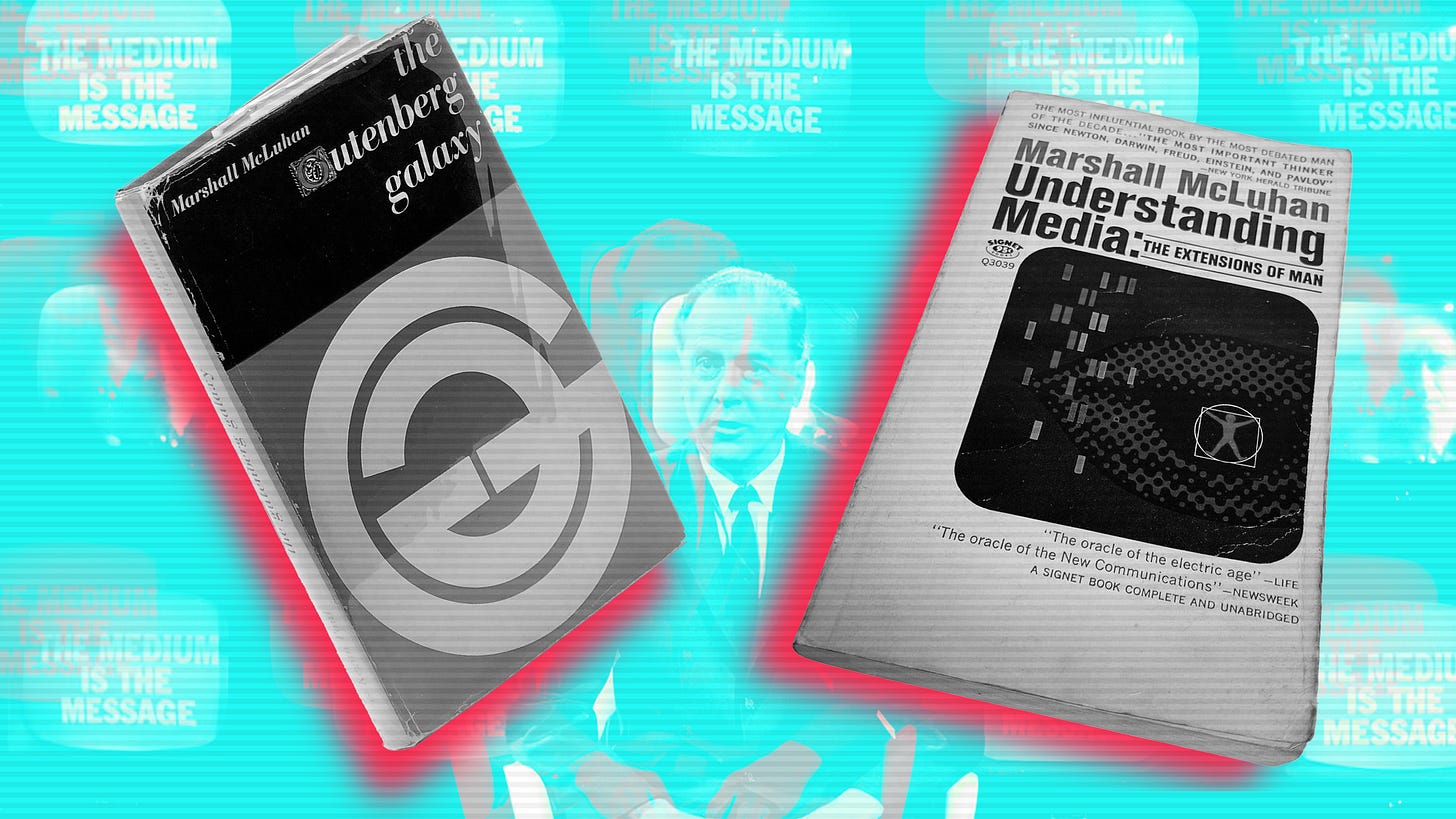

You’d have to go full Freud, whose joke book suggests that the witty, dreamlike compressed paradox of a joke surfaces and economizes transgressive unconscious material for polite society. You’d have to listen to the famed scion of Slowikowska’s Toronto, legendary U of T communications theorist Marshall McLuhan, who called humor “a probe of what’s really going on” that “affords us our most appealing anti-environmental tool… It does not deal in theory, but in immediate experience, and is often the best guide to changing perceptions.”

But you’ve come to the dentist here, and no haterism is going to shield us from the discomfort of the drill. McLuhan was of course the proponent of media determinism, famous for the adage “the medium is the message.” This primary principle of the Toronto School, which McLuhan and fellow professors Harold Innis and Northrop Frye established at the University of Toronto in the mid-20th century, suggests that the sensory effect of a form (for example, the solely visual focus and stress of reading) is more important than its content (for example, the text inside a book). When changes in media are adopted en masse, new technologies exert their own gravitational effect on cognition, which in turn shapes and reshapes social organization.

These are psychedelic, dorm-room stoner ideas. But lost in that bigness is their more practical application in navigating the bewildering social politics of modern life. As we learn time and again, anyone who assumes a governing liberation theology of ‘the moral arc of history bends towards justice’ has a thing or two to learn about how people really think and feel; and anyone who studies how people really think and feel learns through psychoanalysis that language structures the possibilities of even the unconscious mind.

What the Toronto School really does is turbocharge ‘linguistic determinism’ into a broad, variegated, truly modern field of metaphorical ‘languages’ like film, comics, and photographs — or as McLuhan referred to them, ‘media’, the symbolic extensions humankind uses to live and communicate.

What does all this have to do with cringe? For starters, the Toronto School creates a useful shorthand for the participatory latency of social video by making distinctions between between ‘hot’ media like print, radio and movies, which dominate the viewer’s sensory experience, and ‘cool’ media like television and cartoons, which demand audience participation. In the case of the Lore, Rees’ hyper-subjective camera eye isn’t just loudly noticeable, it’s ‘hot’, but the total participatory social video experience and the actors’ performance style isn’t just a mystery to be parsed – Veronika really is cool.

Another relevant Toronto School contention applies ‘medium as message’ to assert the printed word as the cause behind the more-recent-than-we-think phenomenon of modern nationalism. The printing press turned regional dialects into mass vernacular, inventing national movements from Italy to America to France to Haiti and birthing the Fordist factory’s assembly line and modern militarism in the image of the linear, sequential technology of the typewriter.

In the Toronto School view, the pen (or press) is so much mightier than the reactive sword that our world’s entire social and geopolitical climate of the past few hundred years is characterized above all by what McLuhan calls “print-nationalism.” It’s this phrase – dovetailing with the political scientist and scholar Benedict Anderson’s idea of print-capitalism in his classic investigation into nationalism, Imagined Communities – that serves as the structural basis for all that is threatened by the potential ‘video-first’ personhood signified by cringe metafiction.

The dawning of the electronic age, McLuhan prophesied, would spell print-nationalism’s doom, “re-tribalizing” the world into a global village of immediate interconnectedness. Seemingly ironclad institutions like national governments and militaries would reconstitute themselves over the course of decades and centuries like so much silly putty in the hands of our true, new overlord: the evolving structure of electronic communication itself.

And in his time, that vanguard was best represented by a vulgar, small, participatory moving image box called the television.

“The year I graduated, [McLuhan] said, ‘We’re leaving the industrial age. We’re coming into the information age. We thought, ‘No idea what he’s talking about.’ It turns out he was prescient. There were a lot of star professors in those days.” – Lorne Michaels

In many ways McLuhan’s most influential acolyte was a comedy nerd U of T student that once thought himself immune to the Toronto School. In a recent 50th anniversary SNL retrospective in the The New Yorker, Lorne Michaels parses the Toronto School influence on his work pointedly, framing SNL as a highbrow counter-cultural innovation in the new profane mass form, the province of unintentionally cringey soaps and Father Knows Best.

The climactic thesis scene of the recent hagiography Saturday Night suggests Michaels’ signature creative contribution is thinking less of SNL as a comedy showcase than as a participatory imitation of a New York City night out – a conceptual leap that reframes the live theatrical experience as a cool, buzzy ‘event’ for a viewing audience, more real than the real thing. It’s less a comedy insight than a McLuhan-esque masterstroke, ‘saving a trip’ for a national audience looking to partake in electronic allure without ever needing to leave home. Even the studio audience’s heightened state ultimately emanates from an intuitive awareness of the significance of the electronic broadcast.

It’s funny to think that for fifty years McLuhan’s grand ‘print-nationalism vs. electronic age’ battle has been fought at the level of national television comedy broadcast, in a tense dance of soft power between the (print-)national values, customs and politics of the network and the emergent electronic video consciousness of metafictional cringe comedians. Like clockwork, these creators have earned buzz through metafiction and sought recognition by national and linear outlets only to lose the formal edge of the ‘profane’ emergent media that provided the original novel and fresh realist scenarios to parody in the first place.

There is a comical amount of Toronto-adjacent talent who’ve struggled to apply some form of meta-comedy to transcend the company line of national network suits tasked with sustaining print-national order, values and political perspectives. But while the much freer international arthouse has gleefully adopted McLuhan’s fourth wall-breaking perspective in everything from William Greaves’ Symbioectotaxiplasm to Kanoon and Abbas Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy to the great Kaufman/Fincher/Kelly my-first-mindfucks to Torontonian Sarah Polley’s all-timer Stories We Tell, it’s only national broadcast comedy that has truly, slowly, brought metafiction to the masses.

Consider a brief mainstream history of ‘the only new genre of the second half of the twentieth century’, the mockumentary. After the home video of Super 8s and later camcorders kickstarted prosumer tech video literacy, and after Toronto’s best and brightest created SCTV to advance the meta-participation of Michaels’ SNL by building a sketch show around channel surfing, Michaels’ SNL writer Christopher Guest (with the help of SCTV’s Levy and O’Hara), cut loose to permanently dislodge comedy camera perspective from third-person omniscience by popularizing the mockumentary in Waiting for Guffman, Best in Show and A Mighty Wind.

After notable detours in British black comedy (Da Ali G Show, the UK Office), the mockumentary linearized itself for national broadcast by applying familiar soap and sitcom premises to the US Office to make it properly, print-nationally acceptable as “An American Workplace”.

The Office’s example of a soapy “will-they-or-won’t-they” conceit, its return-to-family-values swerve from the UK version (eventually even lionizing Michael Scott’s cringey Father to eventually Know Best), created the new network standard. Now, of course, virtually all network television comedies take place in mockumentary form (anything third-person scans as old, unreal, too fake-official for our video literate intuitive response), while each major mock still possesses the same national values soaps have purveyed since the early days of the boob tube.

So when the late 20th-century internet explosion enabled video viewers to slowly become video communicators on a global scale, the uneasy alliance of the network mockumentary began to show its cracks, forcing cringe television creators to develop more esoteric, committed and extreme forms of metafiction in the now-highbrow TV outskirts as a bridge to users of the free internet like you, me and Veronika.

Adult Swim parodied review and late-night shows to absurdity, with the explosive 12-minute punk album body horror of The Eric Andre Show becoming the first late-night talk show to achieve actual celebrity vulnerability and the On Cinema universe world-building the most meticulous ridiculous longform lore imaginable. Caveh Zahedi’s BTS-themed BRIC web series The Show About the Show took making-of autofiction beyond all reasonable limits, and Good Neighbor matured YouTube parody with a massively influential channel implicitly dedicated to creating cringe vloggers, down to the Final Cut Pro transparency of short king Alex’ pimp fonts.

But only one creator pushed Toronto School ideas to the television brink, using his soapbox to pass the baton to internet video consciousness with the invention of the ultimate identity mindfuck: the proto-cringefluencer. This most innovative McLuhan prodigy also started out with a comedy course at Humber College in Toronto, right after he graduated from business school with really good grades.

I’ve only been to Toronto one time, and it was for a cringe reason: saving Drake’s life in a Nathan for You imitation, applying the Fielder Method to the Fielder Method. What I learned was Nathan Fielder’s real, signature method — not the in-world acting joke from The Rehearsal, but the formal style he originated in Nathan for You. Like an aggressive feint, the real Fielder Method taunts the audience into relating to Host Nathan, a crash dummy of a lead character, only to reiterate over and over that their central attachment is to Filmmaker Nathan, the scenario genius who wears this host identity like the suit from I Think You Should Leave.

Host Nathan is recessive, antisocial and diminished; filmmaker Nathan bold, brash and hilarious. In “The Movement”, for example, Host Nathan limps through a series of deadpan interactions as Filmmaker Nathan sends him into a scenario in which tweaked gym rat Jack Garbarino lies on local news to become the face of a fake workout phenomenon based on moving labor, replete with a forged autobiography referring to his time helping a ‘jungle child named Dende’, before Dende got ‘eaten by baboons’.

By combining Good Neighbor’s Mooney/McCary duo or the mockumentary’s Guest/O’Hara pair into one single character based on his actual identity, Fielder reinvents the cringe metafiction model for the internet age. His ‘double’ is the prototype for an identity that can be incorporated into the solo publishing of any user on a platform profile — say, @veronika_iscool — effectively writing the recipe for making electronic video consciousness mass. Fielder, ultimately, is McLuhan’s imperfect electronic-age vessel: the proto-cringefluencer.

Too ‘hot’ for television, too obsessive, determined and aggressively bold in its filmmaking, the value set indicated by the Fielder Method of course garners intense reaction, with Fielder most often demonized as a manipulative puppet-master. And while his next series, The Rehearsal, is in many ways an attempt to humor this critique, Fielder’s third and most recent work The Curse (shout out to the excellent work done by my longtime friend, the legendary Curse producer Ali Herting) scans as a much more sincere reflection on the impossible role of the television cringe artist within the blood-and-soil politics of the present wave of national reaction.

The story goes: Fielder’s Asher receives a perceived hex from the child of a migrant tenant, unearthing his awareness of his complicity and cucked court Jew extraneousness in the ascendant reality and real estate empire of his wife, Whitney Rhodes(-ia), played by Emma Stone, a sly and insidious manifestation of colonialism reproducing itself to haunt New Mexico and the world. In an epically emo Twin Peaks-ian finale, the “curse” fully manifests itself in Kafkaesque horror-drama reminiscent of previous films of co-creator Benny Safdie, with Asher yeeted into the atmosphere at the moment of Whitney’s reproduction, disposable to the colonizer, enemy of the indigenous, a man without a planet, chosen in all the wrong ways.

Cringe Icarus would seem to have flown too close to the sun. But a persecution fantasy is often a screen, and The Curse hinges on the premise that Fielder’s alienated position is never as alienated as it seems. It’s hard to act next to ‘video man’ Fielder, even for hyper-talented titans of the young Academy like Stone and Safdie, because the laws of gravity do not apply to the crown prince of metafiction.

The secret, of course, is that for a video literate audience, Vertov’s Kino Eye is more relatable than Stanislavsky’s Method. Carrying with him the signature filmmaker/cypher double of his past characters, Fielder possesses a quantum property (The Blessing?) that can only be compressed into the Euclidean three-dimensional space of Paramount+ through the concept of anti-gravity. (No wonder Nolan did the Q+A.)

There’s hardly a place for a proto-cringefluencer within the arbitrary lines of nation-states and national broadcast — ask co-producer Dave McCary, the filmmaker behind Good Neighbor’s eventual SNL transition, who knows a thing or two about linearization — and the inability of the imperfect Fielder to be reduced to the colonial binary proves to be the series’ dramatic core. No matter how compromised, it’s Nathan, as always, who ends up on our side — because we’re all filmmakers now.

Perhaps this is why The Curse, even as a tragedy, scans as so strangely hopeful. While national interests scapegoat international consciousness as a stand-in for international capital (“globalization”), the kino eye of the cringe filmmaker sneakily establishes connection to the deep, lived universalist understanding of every human being. Those who have no place on the ground, we see, will be joined by the camera in the air. The kinetic energy of metafictional cringe will be able to live on, just not on national broadcast; it will have to exist on the free internet; so long as the internet is ‘free’.

PART 3: ESPERANTO

“We are all connected, agha.” – Pirouz Nemati, Ila Firouzabadi and Matthew Rankin

Of course, there were breakout social video accounts of the fall of 2023 much more influential than the Lore trio. Motaz Azaiza and Bisan Owda accidentally and instantly became mega-influencers by simply turning on their phone cameras during the genocidal siege of Gaza. What was so striking was their basic humanity: Motaz and Bisan could, in effect, have been any Palestinian who applied the first-person video of the primary product (smartphone) of the leading American firm (Apple) to simply share the reality of how sausage is made in the outer reaches of the American Empire.

The siege of Gaza activated the inherent untenability of an imperial national posture: a US interest in international markets, not voices, can only work so well when its main product is an amplifier. For audiences in the hundreds of millions, the blatantly obvious reveal of genocidal senility proved a final stake in the heart for the remaining modicum of trust progressive interests held in Democratic leadership, significantly depressing the vote for the Biden-then-Harris presidential campaign to cede the print-national wheel to a nativist right repetition despite the Republican Party’s own milquetoast turnout.

And where there are imperial contradictions, there is an appetite for US intervention, violence as identity quest. Despite the ever-ascendant nat-sec complex’ BRICS bogeyman, it’s of course Motaz and Bisan’s point-of-view that’s most implicitly challenged by the print-national influence of the Tiktok ban-or-sale, Meta “free speech” push and the Musk X acquisition. Tech oligarchs, perceiving the popular vote victory as a market mandate in the proverbial war on woke, have dropped the ‘global citizen’ charade and come home to the DoD from whence they came, rolling out the red carpet for print-national security interests to tip the scales even further on platform content.

Though the video literacy that’s emerged in generations of smartphone users has always come with the precondition of platform austerity, with a robust ‘user mask’ superficially shielding our producer status and the extended trauma of the feudal airlift of ownership, wealth and virtual space to the platform barons, now that ownership closely aligns with the seemingly invincible force of the print-national state, giving it the bully pulpit to linearize emergent technology in the platform era.

It’s worth remembering, though, that social video cringe itself descends from the American anti-capitalist millennial left. Weird Twitter presciently responded to Occupy and early platform optimism with its own strange blend of written dada, as users like Paul Dochney’s Dril deconstructed personal accounts as fictional cringe characters to prod and refuse the directive of platform disclosure, becoming cult entertainers along the way. In many ways the “return of class politics” that arrived after Trump 1.0 demanded a brand of humor that transcended liberal naivete, and the ‘dirtbag left’ gave some postmodern bite to the old-school, civic participatory attitude on offer from the emergent millennial socialist wave exemplified by the DSA, aka the Democratic Socialists of America.

It’s Kentucker Audley’s prestige-indie site NoBudge (short for “no budget”), a counterpoint against tech-augmented media consolidation, where that dada has made the jump to short films. For NoBudge, formal cringe deadpan is a house style. What 368 Broadway symbolically represented for a 2000s mumblecore generation of Gerwig, Safdie, Dunham, Neistat and Nance, NoBudge virtually stands in for the coming wave of Eric Rahill, Kristoffer Borgli, Alex Warren, Mitra Jouhari, Whitmer Thomas, Simple Town, Alex Bliss, Anna Seregina, Edy Modica, Will Duncan and beyond.

The formal deadpan of the NoBudge tone of voice is perhaps best exemplified by NoBudge all-stars Simple Town (performers Sam Lanier, Will Niedman, Felipe Di Poi Tamargo and Caroline Yost and filmmaker Ian Faria). I remember the first time I saw a short of theirs, “Town Meeting”, at a DSA “Paid Protest’ comedy show and screening in late 2010s Bushwick. I’d entered intent on screening my own lefty cringe NoBudge short and left enamored with their work, gathering the distinct sense that smarts-playing-dumb had gone text-to-video.

Simpletons like us — foolish, gullible, provincial — and the repetitive, meaningless inanities of our puritanical, colonial American lives were on full display, with slow, painful long-lens tracking shots, blatantly off old-timey overdubs, winking parodies of Robert’s Rules-style community organizing parliamentary-speak, and the group’s signature repetition of meaningless dialogue. It felt like this collection of largely RISD-graduated artists had done something akin to their Talking Heads predecessors: formalizing malaise into the countercultural medium of the time, except now it was video dada rather than indie rock. This was not my beautiful house, this was not my beautiful wife, this was not my beautiful group chat riffing about Hagrid on SSRIs; the old world was dying, the new one couldn’t be born, and in that futility there was an equalizing hit of truth to the group’s precision focus on the idea that we are all so fucking dumb.

Before the cringefluencer boom, before the Lore, it was on NoBudge where the Lore’s creator trio of Veronika, Kyle and Michael first cemented their signature style on a short called “Love Machine”, now one of the most popular on the platform.

But in the 2020s, the relationship between the ‘dirtbag’ cringe profane and its anticapitalist roots has begun to fray. After a brief but potent lefty resurgence in the popular imaginary, the ‘endgame acceleration’ of liberal reaction, made manifest in the high-profile DNC backroom deal that wedged an incipient Sanders campaign before Super Tuesday 2020, didn’t just turn over into the feckless Biden administration, CoVid pandemic, Palestinian genocide and Trump 2.0 — it deflated the ascendant movement of lefty naifs innovating cringe. It’s as if there was no place for a positive vision to go.

Now, in our vulgar upside-down, the Pete Seeger-cosplay of the Sanders movement appears folksy and naive, while its profane, trickster underside has gone electric with a defiant and irascible post-left trinity of sex, fun and cloutbombing. Camo hats and country have become a bellwether for nativism’s subconscious capture of the ironic set, as left-liberals as high up as the presidential nominee convince themselves they’ve reclaimed the edgy semiotics of January 6th only to find out on November 8th that the opposite is true.

The creature comforts of American life are MAGA’s ace in the hole: even reasonable and responsible ambitions like possessing a steady job with a 401k plan instantly render you a shareholder in American tech. Platform capitalism seems to allow few life options save for the tragic-but-sensible route of building your own small pile and fragmented community: we users fucked around with the phone, and now we are finding out.

Into this incredibly tricky territory, cringefluencers step in for their pinch-zoom close-up. These prestige indie short-filmmakers re-contextualize video dada for the social mass. The biggest strike a balance between video cringe bread-and-butter, unironic thirst traps and brand partnerships for hordes of unfiltered fans in an increasingly hostile corporate climate. While all manner of indie, alt, prestige and left doyennes have fallen out of fashion in the age of media consolidation, everything still keeps coming up cringe – even if the cringe signifier has lost its anticapitalist signified, affect minus ideology.

But our story isn’t about any one cringefluencer – it’s about the form of metafictional cringe itself, and if there’s anything that the Toronto School has to teach us, it’s that where content fails, form succeeds.

“You give them 2+2 and let them add it up.”

– Ernst Lubitsch

Artists are scientists of the soul, and gifted filmmakers have always found media and linguistic workarounds to de jure lines of state propaganda. A relevant example refers back to the infamously puritanical 1930s censorship of the Hays production code. Famously, thanks to director Ernst Lubitsch’s “Lubitsch Touch”, a.k.a his ingenious suggestivity at the level of scenario construction, films could depict lurid sexual scenes without surface violation. Censors “knew what Lubitsch was saying, but they couldn’t figure out how he was saying it,” and his profoundly cosmopolitan effortlessness with visual symbolism and double entendre maintained the edge and ribald sexual energy of his pre-code Trouble in Paradise and menage-a-trois rom-com Design for Living in the post-code era of stone-cold classics like Ninotchka and To Be or Not Be.

The great lesson of Lubitsch is that seduction and meaning occur at the imaginary level, communicated through turns of language (spoken, written, filmic, physical or otherwise) in the great erogenous zone of the mind. Formally encoded ideology, even in a wrapper of reactionary content, is uncensorable.

Because the participatory demand of the ‘cool’ metafiction of video cringe enlists the viewer as a co-conspiratorial fellow filmmaker, print-national editorial control can only go so far. In the long view, it’s less that content is changing minds and hearts than form. And even real life can’t escape the influence of social video metafiction: the new trend in live comedy is the emergence of a clown scene injecting new cringey, physical life into performance after a half-century of rote North American improv. Clown is fundamentally imbued with video consciousness: ‘cool’ performer debasement and a ‘hot’ participatory audience reinterpreting the live theatrical experience through the core elements of social video cringe.

Like camo hats and country, the video slang of cringe co-opts even those who believe they can tame it with a swipe. While capitalists believe in the immovability of the market, fundamentalists in race essentialism and conquest, and Marxists in labor power as the lever to effect change, the Toronto School prophecies around mass adoption of language and new media possess their own robust anti-gravity, because each expansive new way of seeing the world is tough to un-remember.

A recent hallmark event in the Toronto School of anti-gravity occurred when Universal Language, a feature film from Winnipeg’s Matthew Rankin, became the sleeper hit at TIFF. I haven’t seen the film, but I was struck by the way it wittily romanticizes an internationalist vision in its dry, deadpan trailer.

Rankin incarnates a fictional Winnipeg effectively inhabited by the world of Kanoon’s ‘80s Iranian New Wave, weaving in everything Kiarostami-esque short stories straight out of Where Is the Friend’s House? to insane Farsi platitudes-gone-Canadian (“Just as the Assiniboine joins the Red River and together they turn into Lake Winnipeg, we are all connected, agha”) to Rankin himself inserted as a character a la Mohsen Makhmalbaf in Close-Up. The film’s implicit point is loud and clear: Rankin’s Canadian predecessor, Guy Maddin of My Winnipeg, and Kiarostami both spoke the exact same language: the postmodern video slang of metafiction.

“I had this very naive idea that I could go there and study cinema,” Rankin said about Iran’s Kanoon for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. In a recent interview with Denis Villeneuve he even admits that he’s learned a bit of Esperanto, the international auxiliary language developed by L.L. Zamenhof in 1887. Rankin and Zamenhof’s dreams are naive, yes, but naive in all the right ways. The profoundly hopeful and sweet internationalist elements of social video – like the Senegalese creator Khaby Lame being the biggest follow in the world thanks to his Chaplin-esque universalism – show that where the written Esperanto failed to transcend print-nationalism, the true implied universal language – video itself – succeeds.

Across a century of clandestine coups, nuclear brinkmanship and intimidation fracturing human solidarity between North America and Iran, the Universal Language trailer is video proof that in the important way, they’re the exact same place. Look out onto the world and despair over whether we’ll ever be able to experience a semblance of true universal connection on earth; look through the camera lens and see that, in a way, we’re already here.

This essay will be taught at universities

Incredible work here!!!